BlogStories, Research & Projects

|

|

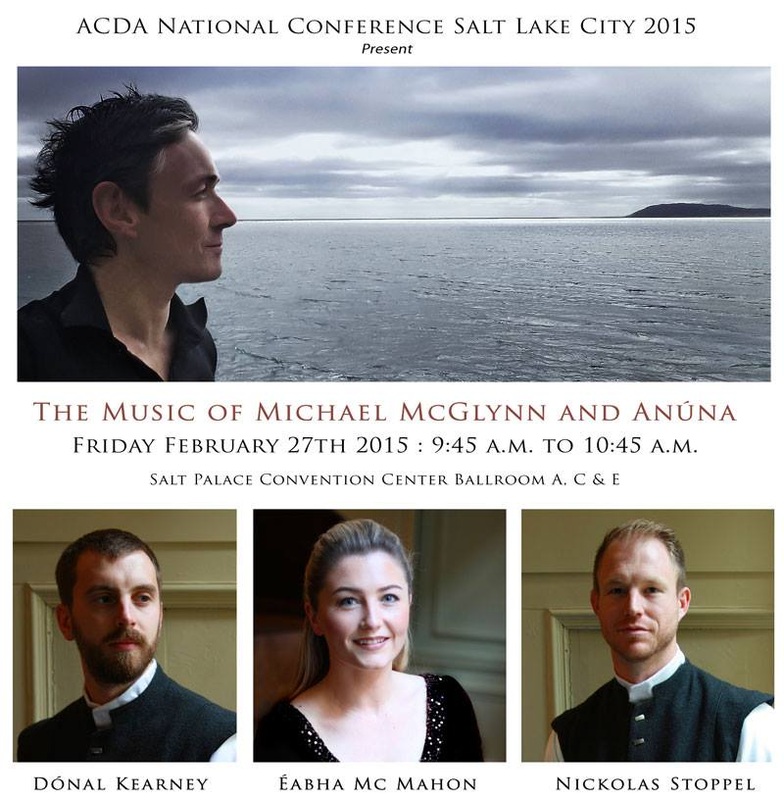

On 27th February 2015, Dónal will co-present at the American Choral Directors Association Conference in Salt Lake City, Utah. The theme of the presentation is "The Music of Michael McGlynn and Anúna". For more information, visit www.anuna.ie.

0 Comments

Dónal is a singer with a background in Law and human rights study. With a degree from the University of Cambridge and a Master's from the Irish Centre for Human Rights, he has worked in many non-governmental organisations and at the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Now he focuses his time on learning about the importance of 'collective singing' and its impact on community identity and cultural expression.

My rights-based advocacy has ranged from student activism and legal studies to international NGOs and the UN, all of which have influenced my attitudes towards civic engagement. The concept of citizenship has evolved in the past decade through the public proliferation of rights-based language in the mainstream press and the democratic digitisation of information online. In recent years, the tension between state power and individual freedoms has surfaced on urban streets across the world. One of my difficulties with human rights theory is the practical implementation of universal human rights norms, whereby certain perspectives are privileged merely due to their traditional authority, economic power, or demographic majority. Perhaps for this reason, I find myself drawn towards local and community-level implementation of rights-based policy. I approach my artistic projects similarly; in terms of place, identity, and the social role of the arts. For instance, how does group singing affect a community? Music, like all art, constitutes an important vehicle for a person to express her/his humanity and philosophy. People from the same place usually have a lot in common, and sharing local stories can help make sense of the human experience. In this way, art can be a bridge between an individual and her/his community. It can bring families together outside of the home, connecting parents and children on equal terms. The arts provide an antidote to alienation and a means of belonging. The Civil Arts Inquiry suggested that it's the stuff that stands out, rather than conforms, that is of cultural import. I would agree that the creative industries, by accessing their capacity for imagination, have a responsibility to confront social problems and explore new channels of participation and cultural expression within marginalised communities. As a singer and educator, I believe every person’s creativity matters. Likewise, every citizen’s participation matters and I view these modes of expression – whether artistic or political – to be connected. I am intrigued by the links between cultural heritage and identity. For the UN Special Rapporteur (SR) in the field of cultural rights, cultural heritage “encompasses things inherited from the past… that individuals and communities want to transmit [to future generations]”. Through culture, “individuals and communities express their humanity, give meaning to their existence, build their worldviews”. Through the arts, parents can educate their children and pass on the values celebrated within their family, which can cultivate an inclusive communal identity. Importantly, the SR also encourages tourism and entertainment industries to respect the right of local communities’ access to and enjoyment of their own cultural heritage. Although the use of public space for cultural events can be a highly politicised issue (especially in divisive societies like Northern Ireland), it is essential in order to foster positive community spirit identity – particularly within marginalised elements of society. Amhráin gaelach tradisiúnta #3This is a children’s song originating from the Donegal Gaeltacht in the north-west of the county. The song tells the story of a small boat owned by a man called Feilimí (Phelim) on a journey to Gola Island, and subsequently to Tory Island, off the coast of Donegal. The song tells the story of Feilimí Cam Ó Baoill, a chieftain of the Rosses, West Donegal in the 17th century. He had to take to the Islands off Donegal to escape his archenemy Maolmhuire an Bhata Bhuí Mac Suibhne. At first, Feilimí sailed to Gola island, which is less than two kilometres off the coast of Gaoth Dobhair. Tory Island was more inaccessible and isolated than Gola island, which is reason enough for Feilimí’s decision to sail beyond Gola onwards to Tory Island. It would provide for a safer refuge. However, Feilimí’s little boat was not sturdy enough and he never survived the journey. Words

Since the 1960s, Gola island (pictured above) has been uninhabited by humans. And to this day, the proud people of Tory Island (below) boast their very own native King! “This remote island, two and a half miles long and three quarters of a mile wide, withstands the full fury of the North Atlantic winter to blossom once again in the soft summer sunlight." Typical of many children’s stories, Baidín Fheilimí is a dark tale; effectively a boat chase, leading to the desperate decision to try to find a better hiding place… and, ultimately, the death of our chieftain hero below the wild Atlantic waves.

|

AuthorDónal Kearney Categories

All

Archives

February 2018

|