BlogStories, Research & Projects

|

|

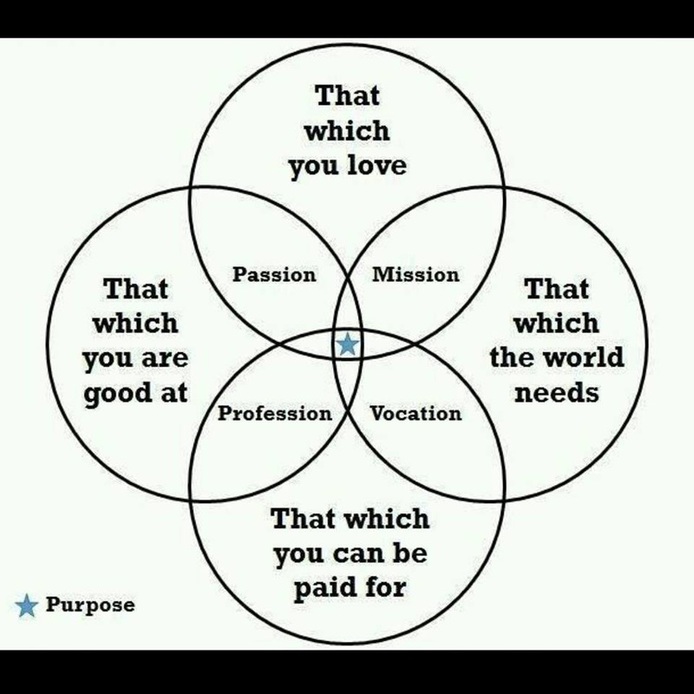

Lunchtime on 26 August at The Fumbally in Dublin 8. I met with a former recipient of support from Social Entrepreneurs Ireland (SEI). Bernadette Larkin encouraged me to consider two things: expanding the scope of groups I’m planning to work with; and documentation. Whereas my initial target group was people affected by a particular social issue (homelessness), I've since opened it up to any group working in the community and voluntary sector. However, Bernadette prompted me to consider working with other groups beyond this – such as schoolchildren. Bernadette’s background is in working with children in the arts. She was supported by SEI in 2006 for her work with Ark in Temple Bar. I spent 27 August devising the following documentation. I also found this cheesy and simplistic diagram on "Purpose" that I wanted to share with you (above).

All of these documents are important for my own project management, but they are also integral to the evaluation process. When approaching potential stakeholders and funders, I want to be in a position where I can demonstrate that I have treated the process professionally and systematically. This is all fairly new to me, but I’m trying my best to learn the processes quickly and efficiently. I want to show that I can adapt my skills and am flexible enough to take guidance and instruction. I know that I don’t know everything setting up a community initiative from scratch. I don’t know much, to be honest! So I’m open to suggestions, of course. Another conversation with my great friend Sophia got me thinking about how to approach schoolchildren, like Bernadette suggested. A former schoolteacher with Teach First, Sophia now works in the UK Civil Service and remains heavily involved in educational practices. From her experience, she knows that there are windows of opportunity for facilitators of programmes that address and explore topics already on the national curriculum. So, for example, there may be storytelling modules for primary schools or music ensemble modules for teenagers that could benefit from a workshop/series such as mine. By tailoring my workshops to particular educational modules, I could spread the benefits of my project in schools across the country rather than just focusing on a limited group (such as individuals experiencing homelessness or human rights advocates). This week has been a real turning point in my project. I also met with Claire, one of the Suas staff who is working on The Ideas Collective. It was very positive. Claire reflected back the concerns and questions that I was voicing in the session and she asked me how I could explore them. She suggested a few ideas and tools and already I am feeling much more confident about my project. This weekend will mark the final weekend session of The Ideas Collective. Then, on Thursday 17 September, we will present each of our projects at a showcase event. It’s all happening very quickly now, but I think I’ll have something ready to launch within a few weeks. Watch this space for updates. And cross your fingers for me...

0 Comments

One of the things I’ve been discussing with singers here at Ulster Youth Choir (UYC) is the concept of cultural rights. Based on my experiences in the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, I'm intrigued by the idea that communities have a legal right to express culture. This may entail a form of protection for art, poetry, music, philosophy, language, songs. This would mean that citizens are entitled to practise these aspects of their native culture without fear of repression – so long as they do not contradict human rights law. Last month, I attended the NUIG International Summer School on the Arts and Human Rights and I was interviewed for the promo video (have a watch below!). Amongst a distinguished crowd, in attendance was Farida Shaheed, the UN Special Rapporteur in the field of Cultural Rights. That was a fascinating weekend and it left me pondering a lot of questions. One of them was: what are cultural rights? CULTURE

At the moment, I define culture simply as “the way we live”. Culture is expressed when we walk the streets and in how we relate to each other in our own homes. It determines how we spend our weekends. It determines what time we sit down for meals and it affects the age at which we are considered fully ‘grown up’. Culture dictates what is an acceptable way to treat another person. This varies between countries, between cities. It even varies between families! I believe that we directly affect our culture and, as individuals, we collectively constitute our own culture. If you choose to smile at someone, you just might influence their mood. If your workplace decides to recycle, you are making an impact on your local environment. If you spend money in fast food franchises, you are perpetuating a culture of unhealthy and convenient eating. Likewise, if you and people in your community decide to act together towards a shared goal, you are creating your own culture. You are contributing to your own local memories and traditions. Art both reflects and influences culture. As art evolves, so too does culture. New songs are written and some of those new songs become classics over time. New composers emerge and new styles break through. Culture is far from static – it lives and grows. If we realise this and consciously see ourselves in the context of our own community, each with a participative role, we can take responsibility for our own actions and commit to a meaningful and productive sense of belonging. You have to ask yourself what type of society you want. Do you want an individualist, competitive economy? Do you want a communal, equal world? Do you want a fair meritocracy? Do you want a world of diversity and shared experiences? Do you seek an anarchist existence whereby people self-regulate and self-govern? Do you want to be as powerful and wealthy as possible, knowing that everyone else might want the same thing? Do you want a utopia of peace and harmony? Whatever the answer, its creation boils down to simple acts. For example, supporting local trade; taking pride in clean streets; caring for a shared garden; running your own farm; contributing to community initiatives of all sorts; facilitating experiences for young musicians, etc. Of course, culture can be created on a small scale. It can start in your home. It can spread to the street you live on. Or maybe your village. Even a workplace can have its own culture. You impact the community you associate with, and you’d be surprised how many people you can influence over the period of a week. My point is that you can create your own culture from within. The way I see it, culture is not necessarily something that affects you from outside. Bearing all this in mind, another question presents itself. Would the legal protection of cultures around the world function effectively as a long-term method of conflict resolution or peacekeeping? POST-CONFLICT SOCIETIES I think it could work as a way of addressing cultural conflicts, providing a judicial forum in which to mediate cultural clashes. In conflicting societies, art is an important outlet for opinions that might not be tolerated in the mainstream. It’s a creative and expressive form of communication. This is often essential in situations of cultural conflict. To take an example very familiar to me, Northern Ireland is the site of an ongoing cultural conflict. This is played out in the media and, thankfully, is largely non-violent. It manifests in Stormont and in the Parades Commission and in Belfast City Hall. It erupts at urban sectarian interfaces in Belfast and a few other locations across Northern Ireland. The problem with many political entities, including Northern Ireland, is that the system is tied to nationalistic governance. Post-conflict societies where violence has mainly been abandoned invariably tend to expose the inadequacies of Nationalism. In Northern Ireland, political parties exist as one of three persuasions: Nationalist, Unionist or Other. Where power is divided along these stark lines, it’s no surprise that citizens are pitted against each other and we're left with a tense and uneasy democracy, battling against threats to our perceived identity. The language of cultural rights was included in the Bill of Rights for Northern Ireland, one of the outcomes of the Belfast Good Friday Agreement 1998. In the 17 years since, no action has been taken by authorities to implement the Bill of Rights as legally binding. If cultural rights were legally binding, the “particularities” of Northern Ireland’s circumstances would produce jurisprudence on issues such as symbols and flags, parades and commemorations, and the issue of language. These are each very divisive topics in Stormont today, and the current consociational power-sharing government is ill-equipped to address the conflicts arising out of the status quo. With a legalistic approach to cultural rights, new ways may be discovered to mediate conflicts between opposing nationalisms (in this case, British and Irish). I've seen how cultural expression can strengthen community identity. Singing songs that bring people together (rather than ones which promote political or social superiority) is a beautiful way to express oneself. We should promote positive and communal aspects of local culture. This does not require that we sacrifice uncommon ideas, but it does mean working hard to perpetuate useful and non-divisive elements of culture. In a democracy, this is imperative. Perhaps disassociating with nationalism and promoting localism is an appropriate way to start doing this. It requires that you live according to your convictions rather than compromising your values in favour of the status quo. Start at community level. Ask yourself (your family, your friends) what type of society you want to live in. Then make it together. Your actions will inevitably affect your community and its culture, and it will change; very slowly, probably imperceptibly. And, most likely, things won’t end up how you thought. Perhaps, over a period of time - a generation or two - you’ll actually have created something close to the society you wanted. It’s up to you.  For the past fortnight, I’ve been working in Belfast on the residential courses of the Ulster Youth Choir (UYC) and the Ulster Youth Training Choir (UYTC). The age of the singers on the courses ranges from 14 to 22. It’s been a wonderful time for me, and it’s really pushed my thinking about my project through The Ideas Collective. My role has been as a Pastoral mentor, which involves child protection training, dealing with homesickness or physical injuries, bullying (thankfully there have been very few problems!), enforcing course policy, etc. I find it really interesting work because I’m learning so much from the young singers themselves – about how they respond to the music, about what experiences they enjoy, and about what musical theory/knowledge is required to sing at this musical level. Of course, I'm also learning a lot from the music staff on the UYC course: about how to approach a large group of young musicians with demanding repertoire and about what they’re looking for in the UYC sound. Every day I spend here, it brings me back to my time in UYC. I joined the choir first when I was 14 and did a second course aged 15. I loved it and I took away so much. It was the first time in my life that my eyes were opened to the effect that collective singing can have on a group of people. To be honest, one of the main things I remember is the confidence it gave me. As a young man, I was working out my own strengths and weaknesses. As young singers, we engaged collectively in a way that we will never forget. Chris Bell, the conductor in my first year, commanded so much respect from the group that everyone tried to win his favour at every moment of rehearsal. Even if we don’t remember people’s names (or their faces!), we still remember the emotion of creating that music together. I remember the beauty of Mendelssohn “Kyrie Eleison”. I remember how it made me feel to sing Vaughan Williams’ “Through Bushes and Through Briars”. I remember being brought to tears by McMillan’s “The Gallant Weaver”. The other day, I found the album UYC recorded during my time, entitled “The Singing Will Never Be Done”. It includes three pieces by Anúna’s director/composer Michael McGlynn. This was my first time singing McGlynn’s music. It was a special time. UYC means a lot to me. And now I’m on the other side, trying my best to make sure these young singers are getting as much out of it as I did. I’m very proud to be a part of it. The courses have given me plenty of food for thought regarding The Ideas Collective. When I am working with participants on my project, my aim is to bring individuals together in a creative environment to build a community of human rights advocates: people who will voice their concerns and stand up for themselves; people who will confidently develop a community together and become leaders in their own right. We hope to achieve this through music. |

AuthorDónal Kearney Categories

All

Archives

February 2018

|