BlogStories, Research & Projects

|

|

John McCambridge (aka. Seán Mac Ambróis) had a passionate interest in the Irish language, which was spoken by most of the natives in the Glens in the mid-19th Century when Airdí Cuan was written. The song is named after a place near Cushendun. According to the map below, the townland of 'Ardicoan' lies between Bunavoher and Clady Bridge to the north on the Glendun Road. In many ways, the people of the Antrim coast look towards Scotland as much as to the rest of Ulster. The Scottish connection is emphasised in local surnames such as McAlister, McKay, McNeill and common forenames like Alasdair, Randal and Archie. According to researcher Seán Quinn, "traditional culture survived well in the Glens of Antrim because of their remoteness and the Irish language was spoken daily around Cushendall until the early 20th century. Féis na nGleann was founded in Glenariff in 1904 under the inspiration of the celebrated Belfast folklorist and historian F. J. Bigger. There were competitions in language, traditional music and dancing as well as athletics and hurling. The Féis was maintained by the Gaelic League (Connradh na Gaeilge) which fostered the 20th century revival of national culture throughout Ireland. This enthusiasm for traditional culture has survived into modern times, and there are many notable singers and musicians associated with this area." The townland of Ardicoan is a mile west of Cushendun, rising north from the River Dun to a height of about 500 feet. There is a multiplicity of Gaelic versions of the placename, and an equal multiplicity of interpretations: Airdí Cúing, Ard a’ Chúíng, Aird an Chúmhaing, Ard a’ Chuain, Airdí Chuain, Ard Uí Choinn. The first element, no matter how it is spelt, probably means a height. Dr Pat McKay of the Placenames Project in Queens University Belfast says that there is no authoritative version of the name, but tentatively recommends Ard a’ Chuain – the height of the harbour, or the height of the bay (Cuan in Scottish Gaelic also means the sea). Seán Mac Maoláin argues for Áird a’ Chum[h]aing (= the height of the narrow strip of land) because the townland is well back from the sea, and follows the narrow defile at the head of the glen, reminds us that the noun ‘cúng’ also means a narrow defile between two heights. The townland itself is long and narrow, and there is an Alticoan in the next glen. John McCambridge was born in 1793 in Mullarts, near Glendun, and died in 1873. He is buried in Layde churchyard between Glendun and Glenballyeamonn. His tomb is partly in Irish. McCambridge was a native of Mullarts between Cushendun and Cushendall (at the bottom of the map) and recent research suggests that he belonged to a fairly affluent Presbyterian family. The story of Airdí Cuan is told from the perspective of a Glensman who has moved over the sea to Scotland. From Ayrshire, he can still see the hills of Antrim and he longs for his home in Glendun and the beautiful hillside at Airdí Cuan. One story goes that McCambridge left his native Glendun, perhaps to escape the potato famine, and settled in Ayrshire where he ultimately died pining for the hills of home, still visible on the western horizon. Airdí Cuan tells of his love for the 'cuckoo glen'; (Glendun) and of playing hurling at Christmas on the 'white strand' (the beach at Cushendun). Another school of thought believes that, while McCambridge was considering emigrating to the Mull of Kintyre, he stood atop Ardicoan and imagined himself over in Kintyre looking back on his native soil. However, the process of writing the song made him so homesick that he decided not to go in the end, and thus spent the rest of his days in Ireland! Which of these stories is accurate (if any!), and whether or not the song is autobiographical, I'm not sure. I still have to do more research! Make sure to click play on the videos below while you're reading the song's text.

Here are a few version online. Over on Spotify, Anúna's world-shattering arrangement is well worth a listen. Below is another of my favourite versions of Airdí Cuan, recorded by Doimnic Mhic Giolla Bhríde's Cór Thaobh a' Leithid from Gaoth Dobhair in Donegal.

2 Comments

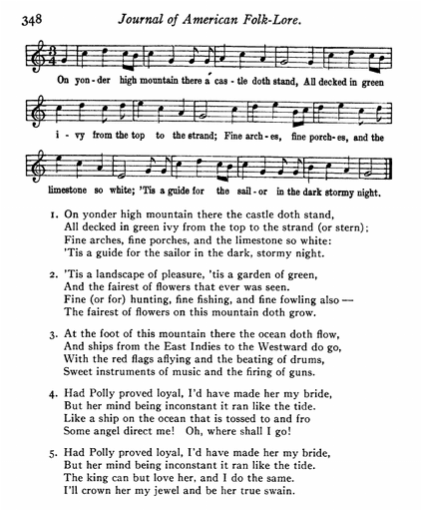

The Newry Mountains lie about 2 miles west of the town of Newry in Northern Ireland. They consist of Slieve Gullion (1,880 feet), Camlough Mountain (1,385 feet), and Ballymacdermot Mountain (1,019 feet). Slieve Gullion takes its name from the Gaelic Sliabh gCuillinn meaning "mountain of the steep slope”. It is one of the finest detached mountains in the kingdom, separated from Camlough Mountain by a deep valley, and rises abruptly from the plain known as the Ring of Gullion, an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). Near the top of Slieve Gullion is a small, deep lake, and on the very summit of Slieve Gullion are two ancient burial carns. One of these was an artificial cave formed of dry masonry. It is thought to be the highest surviving passage grave in Ireland (pictured below). According to local legend, an enchantress dwelt in this cave, the fairy daughter of Culand, the mythical smith of the De Dannan. Camlough Mountain is also known locally as Newry Mountain, or “Slieve Girkin”, which possibly derives from Sliabh gCuircín: 'Mountain of the little crest’. I have found a song known by many titles over the years, but the most recent version I have come across is called "On the Top of Newry Mountain". "On the Top of Newry Mountain" LYRICS Oh, I wrote to you, Nellie, what makes you prove kind? What makes you pull that lily, leave that red rose behind? For the lily it will fade and the time will come soon but the red rose will flourish in the sweet month of June. Slieve Gullion is a mountain, its stands in great fame at the top of Newry Mountain it bears a great name For a-hunting and a-grousing and a-fowling also and the best of bilberries on that mountain does grow. On the top of Newry Mountain, a castle does stand It is bound round with ivy from the top to the brim It is bound round with ivy and a marble stone bright, It’s a pilot for sailors on a dark stormy night Not far from Newry Mountain, sure, a river does flow and the ships that sail upon it into Newry will go Where the green flags are waving to the beating of drums and instruments play music ‘midst the firing of guns. Sure, if I was in Newry, I would sigh I was home for there I have a sweetheart but sure here I have none Kind sweetheart, kind sweetheart, what makes you prove kind that you wait on a young man, not knowing his mind. History of the SongThis song has a fascinating life-span. According to one online source, a version of was first collected in 1893 as English folksong “Faithful Emma” (Broadwood/Maitland). It is believed to share one verse with another English song, "The Streams of Lovely Nancy": At the top of this mountain a castle does stand / It is decked round with ivy and back to the strand / It is decked round with ivy and marble stone white / It's a pilot for sailors on a dark stormy night. Below are the lyrics of “Faithful Emma”, which are very similar. According to Broadwood/Maitland writing in 1893, this text is either the beginning and end of one ballad, or the first three verses of one tacked on to the ending of another. At the top of yonder mountain, where my true love’s castle stands It’s all overgrown with ivy from the top down to the strands Fine arches, fine porches and diamond stones so bright It’s a pilot for the sailors on a dark and stormy night At the bottom of this mountain, there’s a river runs so clear And a ship from the West indies she did once anchor there With her red flag a-flying and the beating of her drum Sweet instruments of music and the firing of her gun If little Mary had proved faithful, well, she might have been my bride. But her mind it was more fickle than the rain upon the tide Like a ship upon the ocean that is bobbing to and fro And the angels might direct her wheresoever she may go. In 1917, the same song is published as “On Yonder High Mountain” in ‘Ballads and Songs’ (ed. G L Kittredge) in The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. XXX, No. 117, pp. 347-348 (Jul-Sep 1917 - available online by JSTOR). Kittredge's version was communicated in 1914 by Professor Angelo Hall of Annapolis, Maryland. He had learned the sung from his aunt, Mrs Elmina Cooley, who died twenty years before. In turn, Mrs Cooley got the song from her father, Theophilus Stickney from Jaffrey, New Hampshire, before 1833. The words and tune were printed in a biography of Professor Angelo Hall's mother in 1908. By this stage, the lyrics have been changed to mention “green flags” rather than “red flags”. An archivist called Helen Creighton made recordings with an Irish-Canadian singer called Angelo Dornan. In a recording dating from c. 1954, Dornan sings a song for her named "Nellie". The version closest to Dornan's melody and text is found in the Irish Traditional Music Archive. The song, now called "On the Top of Newry Mountain" was sung in 1988 by Jim McGonigle’s in Buncrana. Maybe the most noticeable difference is that Dornan’s version is in a minor mode, whereas McGonigle sings it major. O Nellie, O Nellie, what makes you unkind? For to choose the lily, leave the red rose behind? For the lily will fade and the time will come soon When the red rose will flourish in the sweet month of June Oh, Slieve valiant mountain, it bears a great name And beyond lunar mountain, it is fair to be seen With hunting and fowling and grazing also And the finest of blueberries on this mountain do grow. At the top of this mountain, a castle does stand, It is decked round with ivy and back to the strand It is decked round with ivy and marble stone white It’s a pilot for sailors on a dark stormy night At the foot of this mountain, the ocean does flow And the ships that sail on it to Newry do go With a green flag a-flying and the firing of guns All instruments of music and the beating of drums If I were over Newry water, I would think I was home For it’s there I have a sweetheart, but here I have none Oh, sweetheart, oh, sweetheart, what makes you unkind? But you are far from me and you know not my mind. The song I refer to as “Newry Mountain” is borne out of this mixture of songs. However, as well as the differing lyrics, the melodies too are varied. This is not surprising, given that collectors of songs would have collected melodies/airs and lyrics separately. Therefore, texts of songs were gathered independently of their tune, and inevitably singers did with them what they wished. The mention of the green flags (which used to be red flags earlier in this song's life) in the fourth verse of the song is a possible reference to the United Irishmen’s campaign against the state. The beating of drums and firing of guns may be a direct reference to the 1798 rebellion in Ulster, thus placing the song's characters in the late 18th century. Therefore, the castle mentioned in the song might be compared to Moyry Castle (above, right) or to Killeavy Castle. Mythology of Newry MountainAccording to one local story, Áine and her sister Milucra both sought after the legendary hero Fionn MacCumhaill. When Áine said she would never marry a man with grey hair, Milucra secretly put a spell on the lake, so that anyone who swam in it would emerge as an old person. She tricked Fionn into swimming in it, and he emerged as an old man with grey-white hair. His soldiers, the Fianna, forced Milucra to feed him a restorative potion from her cornucopia (a large horn-shaped container). Although his youth was restored, his hair never returned to its true colour. In some versions of the tale, Milucra is revealed to be the Cailleach Bhéirre, a powerful hag believed to be the Winter Queen in Gaelic Scotland and Ireland. She reigned from Samhain until Béaltaine (November to May) each year and created mountains with her magic hammer. According to Scottish folkore, Beira was a one-eyed giantess with white hair, dark blue skin, and rust-colored teeth. Several features on Slieve Gullion refer to the Cailleach Bhéirre. The passage grave at the top of the mountain is known as Calliagh Birra's House and the small lake is called Calliagh Birra's Lough. Lower down, on a hillock called Spellick, is a rock feature called the Calliagh Birra's Chair. Locals visit it at the summer festival of Lúnasa and take turns sitting on the chair. Slieve Gullion also plays a key role in the legend of Cú Chulainn. According to mythology, the mountain is named after Culann, the metalsmith. The legend goes that a boy named Setanta spent his childhood in the mountains of Newry. He would later receive the name Cú Chulainn. Culann invited Conchobhar MacNeasa, King of Ulster, to a feast at his house on the slopes of Slieve Gullion. On his way, King Conchobhar stopped at the playing field to watch the boys play hurling. He was so impressed by Setanta's performance in the first half that he asked him to join him at the feast. Setanta promised to join him once the match was over. King Conchobhar went ahead to the feast and began to enjoy the festivities. After the first course, and much wine, he forgot to mention his invitation to Setanta to his host, and Culann let loose his ferocious wolfhound to guard his house, as was usual for such an occasion. Setanta ran all the way to the house after the match, hurl in hand. Threatened by Setanta’s pace, the guarding hound attacked Setanta on sight. Out of instinct, Setanta stooped to lift a rock the size of his fist as the hound lunged at the boy, tongue and razor-teeth on show. With the single fluid motion of a natural athlete, Setanta hurled the rock through the jaws of the oncoming dog at the last second. Setanta’s puck was so powerful that it dragged the huge animal’s head backwards, breaking its neck and crushing its skull. The hound was killed instantly. Moments later, one of the King's soldiers came across the scene and fetched the host from the feast. Culann was devastated by the loss of his loyal hound, so Setanta promised to rear him a replacement as he cared for some local wild dogs himself. Until one was old enough to do the job of guarding King Culann, Setanta offered to guard the house. A druid present, known as Cathbhadh, announced that his name henceforth would be Cú Chulainn, "Culann's Hound". This story is very well known around Newry. The Lily and the RoseIn the first verse of "Newry Mountain", the poet introduces the lily and the rose. According to the science of flower language (florigraphy), romantic lovers began using floral exchanges to convey emotional messages using the flower meanings. The Victorians became very knowledgable in the flower language and chose their bouquets carefully. Flowers gave them a secret language that enabled them to communicate feelings that the propriety of the times would not allow, there were strict restraints on courtship and any displays of emotion. Flower selections were limited and people used more symbols and gestures to communicate than words. Roman mythology associates the lily with the goddess, Juno. While nursing her son Hercules, excess milk fell from the heavens. Some remained in the sky, creating the Milky Way, and some dropped to earth, creating the lily. In ancient Rome, lilies were known as rosa junonis, or Juno's rose. In classical mythology, it was believed that all roses were white in the beginning. In ancient Greek mythology, it is told that when Jupiter saw Venus bathing, she blushed with great embarrassment and all the white roses nearby were turned red in sympathy. In the first verse of “Newry Mountain”, the poet asks Nellie, his lover, why she prefers to pick the lily rather than wait for the rose? In Irish folklore, the lily is thought to represent May or Springtime, while the red rose blooms in Summer and is associated with June. In florigraphy, the white lily is recognised as a symbol for purity, innocence or young love, whereas the red rose is recognised as signifying passionate love. With this insight, we can reasonably assume that the lily in the song refers to Nellie’s first love, probably the poet. The poet asks why Nellie stays true to him when he is no longer in Newry (“what makes you prove kind?”) when she could pursue the red rose of another lover instead. She could have a love that is passionate and real, rather than one that is pure, innocent and absent. Indeed, the poet’s commitment to Nellie is dubious – he is a self-confessed “young man / not knowing his mind”. This opening and closing verses address the relationship directly, whereas the middle verses speak only of the poet’s memory of Newry. I think his relationship to the mountain is more passionate than his fondness of Nellie.

Not much more than this is available online about the history of the song, but it is an interesting text that employs physical features of the locality – the ocean, the mountain, the castle. It alludes to themes of youth, love and war. The most interesting aspect of the song for is the questions it raises: who adapted the lyrics in the first half of the 20th century? Who inserted the mention of Newry? Was it a local person? Or was it a visitor? Who was Nellie? It is a beautiful document of local lore, and I can’t wait to learn more about the song. In 1888, a German linguist called Wilhelm Doegen travelled to a Prisoner of War (POW) camp in Giessen, north of Frankfurt. Doegen was conducting research on the language, music and songs of the prisoners of war captured by the Germans during The Great War 1914-1918. On 27 September 1917, Doegen recorded a man singing an Irish song in Giessen POW camp. Belfast-born shoemaker John McCrory (36) sang "The Pride of Liscarroll". It can be heard on the BBC website, or the digitally enhanced audio can be played via The Irish Times Soundcloud account here. This song tells a heart-warming tale of a local girl in Cork, whose community looks after her after a tragic accident involving the death of her lover. It really is quite a lovely story. The song is also known as "The Blind Irish Girl", "Sweet Kitty Farrell" or "Katie Farrell". In our native town Liscarroll there dwells a colleen who was blind And they called her Katie Farrell to her the neighbours all were kind To see her knit beside her mother you never would think her sight was gone And with Barney her young brother she milked the cows at early dawn She’s the pride of Liscarroll this sweet Katie Farrell With cheeks as red as roses and teeth as white as pearl And the neighbours all pity that colleen so pretty And oh how we all love that blind Irish girl Well years ago when Kate were courting her young lover Ned Molloy One night as they were both out walking with hearts like children full of joy A storm arose and Kate got frightened she seized the arm of sweet heart Ned And they both were struck by lightning they found her blind and he was dead She’s the pride of Liscarroll this sweet Katie Farrell With cheeks as red as roses and teeth as white as pearl And the neighbours all pity this colleen so pretty And oh how we all love that blind Irish girl. Other versions of this song can be found on the Irish Traditional Music Archive website. On the same day, Doegen recorded a man called Private James McAssey from Leighlinbridge, Co. Carlow, as he sang a song called "No One To Welcome Me Home". A version of this was collected by Clare County Library, in which there is no mention of Ireland whatsoever. It's interesting, therefore, that the chorus in McAssey's version goes: "No one to welcome me home, far away / No one to welcome me home / For it's when I'll return to old Ireland again / I'll have no one to welcome me home." In the twilight I wandered alone, Far, far away from own native home. Fatherless, motherless sadly I roam: I’ll have no-one to welcome me home. I’ll have no-one to welcome me home far away, I’ll have no-one to welcome me home. And when I will return to the land of my birth, I’ll have no-one to welcome me home. ‘Tis well I remember that little brown cot In old Ireland far over the sea. That little brown cot in the top of the hill, Where my mother stands waiting for me. Saying, ‘Me boy you are bound for a strange land to roam, And you’re leaving me here all alone. If you ever return to the land of your birth, You won’t have me to welcome you home.’ I’ll have no-one to welcome me home far away I’ll have no-one to welcome me home. And when I will return to the land of my birth I’ll have no-one to welcome me home. My mother she stood at the quay all alone, With a handkerchief up to her eyes. As she watched the big ship sailing out with the tide, It was then she began for to cry. Saying, ‘Me boy, take this locket a gift now from me, And inside there her photo was placed. And these were the words she embraced with a sigh: ‘You won’t have me to welcome you home.’ I’ll have no-one to welcome me home far away, I’ll have no-one to welcome me home. And when I will return, to the land of my birth, I’ll have no-one to welcome me home. Another version of this song, with slightly altered melody and lyrics, is called "Emigrant's Lament" and talks about an English emigrant working in the Colorado coal mines. Listen to James McAssey sing it on 27 September 1917 here. The final song in the recordings is "Where The River Shannon Flows", sung by Waterford man, Private Edward Duggan. Listen to him sing it here. There's a pretty spot in Ireland I always claim for my land Where the fairies and the blarney will never, never die It's the land of the shillalah My heart goes back there daily To the girl I left behind me when we kissed and said goodbye CHORUS: Where dear old Shannon's flowing Where the three-leaved shamrock's grows Where my heart is I am going to my little Irish rose And the moment that I meet her With a hug and kiss I'll greet her For there's not a cailín sweeter where the River Shannon flows. The Irish Times has written a fantastic piece on these POW tapes entitled The Soldiers' Songs. I encourage anyone interested in the singers - the soldiers themselves - to have a read.

|

AuthorDónal Kearney Categories

All

Archives

February 2018

|