BlogStories, Research & Projects

|

For the past fortnight, I’ve been working in Belfast on the residential courses of the Ulster Youth Choir (UYC) and the Ulster Youth Training Choir (UYTC). The age of the singers on the courses ranges from 14 to 22. It’s been a wonderful time for me, and it’s really pushed my thinking about my project through The Ideas Collective. My role has been as a Pastoral mentor, which involves child protection training, dealing with homesickness or physical injuries, bullying (thankfully there have been very few problems!), enforcing course policy, etc. I find it really interesting work because I’m learning so much from the young singers themselves – about how they respond to the music, about what experiences they enjoy, and about what musical theory/knowledge is required to sing at this musical level. Of course, I'm also learning a lot from the music staff on the UYC course: about how to approach a large group of young musicians with demanding repertoire and about what they’re looking for in the UYC sound. Every day I spend here, it brings me back to my time in UYC. I joined the choir first when I was 14 and did a second course aged 15. I loved it and I took away so much. It was the first time in my life that my eyes were opened to the effect that collective singing can have on a group of people. To be honest, one of the main things I remember is the confidence it gave me. As a young man, I was working out my own strengths and weaknesses. As young singers, we engaged collectively in a way that we will never forget. Chris Bell, the conductor in my first year, commanded so much respect from the group that everyone tried to win his favour at every moment of rehearsal. Even if we don’t remember people’s names (or their faces!), we still remember the emotion of creating that music together. I remember the beauty of Mendelssohn “Kyrie Eleison”. I remember how it made me feel to sing Vaughan Williams’ “Through Bushes and Through Briars”. I remember being brought to tears by McMillan’s “The Gallant Weaver”. The other day, I found the album UYC recorded during my time, entitled “The Singing Will Never Be Done”. It includes three pieces by Anúna’s director/composer Michael McGlynn. This was my first time singing McGlynn’s music. It was a special time. UYC means a lot to me. And now I’m on the other side, trying my best to make sure these young singers are getting as much out of it as I did. I’m very proud to be a part of it. The courses have given me plenty of food for thought regarding The Ideas Collective. When I am working with participants on my project, my aim is to bring individuals together in a creative environment to build a community of human rights advocates: people who will voice their concerns and stand up for themselves; people who will confidently develop a community together and become leaders in their own right. We hope to achieve this through music.

0 Comments

The High Hopes Choir is a group of singers who are united by their experiences of homelessness. The original RTÉ documentary features choirs from Waterford and Dublin. On Monday evening, my request to attend the Dublin rehearsal was accepted. The Focus Ireland staff I dealt with were so accommodating and I really enjoyed being witness to this group at work. When I walked into the northside chapel where they rehearse, I was greeted by about 20 seated singers engaging in the usual pre-rehearsal chit-chat. Feeling very much the outsider, I was soon welcomed by Glenn of Focus Ireland and the choir master, Carmel Whelan. Although I was completely unaware of who was taking the High Hopes Choir since David Brophy stepped down in December, I met Carmel for the first time a few weeks ago! She was a delegate at the 3rd Anúna International Summer School, which took place in Dublin from 24th - 27th June 2015. We had 50 delegates from 14 different countries. I was a facilitator of that Summer School, so it’s a strange coincidence then that I walked in on her working with her own choir. I suppose that’s Dublin for you! Carmel got to work warming up the voices that had had a week off. Normally, the group meets every Monday, but due to illness, the previous week’s rehearsal had been cancelled. This is a very uncommon occurrence, but I was told that it can have a knock-on effect in attendance. The singers are used to the routine, and upsetting this routine can be a put-off. Right enough – numbers were down from the 35-strong choir that usually turns up. It is fantastic to see the commitment of these individuals and the ongoing drive to make music. For any musician, this is everything. It's all the more inspiring due to the obvious hardships that go hand in hand with homelessness, the extent of which most of us cannot begin to fathom. The High Hopes Choir works according to the direction of a committee made up of the singers themselves. Focus Ireland, the Dublin Simon Community and St. Vincent de Paul collaborate on the choir, but decisions are taken internally amongst the singers. And they are in demand! Performing at Áras an Uachtaráin last weekend – a week before our Nova Collective gig there – and looking forward now to a set at Electric Picnic. The thing I noticed most was the concentration and intent during rehearsal. And the laughter. They all seemed to be having a great time. They’ve created a community and a purpose. This is what singing together is all about: unity. I hope to remain involved in some capacity with the High Hopes Choir. I left the place on a buzz. There are so many community arts initiatives of value and the High Hopes Choir is certainly making waves.

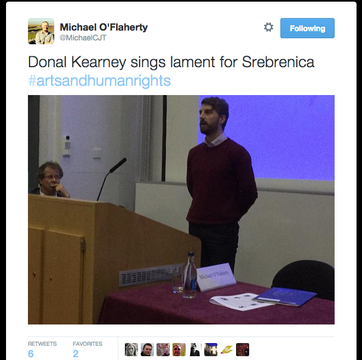

Carmel asked me to sing a song before I left. After all, they’d let me sing with them. I chose to sing The Sheepstealers. That song tells a story about a man doing something that he knows is wrong. But he does it because he has to.  Last week, I attended the NUIG International Summer School on the Arts and Human Rights. As an alumnus of the Irish Centre for Human Rights, I was very comfortable returning to discuss issues of international human rights law. This time, the rights theory was infused with artistic critique. The closest thing I’d come to this combination previously was during the Human Rights Council at the OHCHR, Geneva, when artists advocated for civic freedoms through the practice of their work. I came across countless artist human rights defenders in my work with Front Line Defenders in Dublin. There are people across the world using their talent, their energy, and their time to promote the human rights of others. This is all the more admirable in states where the statements made by the artists breaches domestic law. For example, a rapper who records a track lambasting government policy may find herself subject to criminal proceedings in some east Asian states. The NUIG Summer School looked at the interface between artistic and human rights practices. In attendance were legal practitioners from across the world, current and former UN Special Rapporteurs, heads of international NGOs, academics in the field of human rights, as well as high-profile musicians, artists, curators and producers. An eclectic array of opinions served up a fascinating discussion over the two days I attended (I missed the opening day thanks to a wedding gig in Newry!). On the second day, I was selected to present in the workshop on Music and Human Rights on the theme of “Belonging”. The facilitators were Executive Director of Musicians for Human Rights, Julian Fifer, and former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Manfred Nowak. Fair play to NUIG for assembling such an awesome team! My presentation addressed the power of song in the process of fostering a shared identity and community-building. Of course, songs can divide as well as unite – and this was one of the first questions that came back at me once I’d finished the presentation. I’ll be completing a document on my presentation, so I will post it on this blog in coming weeks. Indeed, an emerging theme of the Summer School on “Belonging” was how readily the debate turned to Exclusion. With any in-group, there is an out-group (‘the Other’). Art plays a role in bringing people together, but it can also pit communities against each other – especially in examples such as nationalistic imagery, songs in a particular language, or openly sectarian music such as that broadcast in Rwanda in 1994. For instance, singing in the Irish language arguably excludes those who do not understand the lyrics. An interesting topic of discussion might be to consider art that does not exclude, but rather includes everyone in a society. Please contribute in the comments below if you’ve any immediate thoughts! On the third day of the Summer School – 11 July 2015 – the Summer School marked the 20th anniversary of the Srebrenica massacre. Between 11-13 July 1995, Bosnian-Serb forces entered what was thought to be a UN-protected “safe area” in Srebrenica. Within a matter of days, 8000 Muslim Bosniaks had been murdered in what is considered to be the worst military atrocity since the Second World War. After a lecture given by Manfred Novak on the significance of music during the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Professor Michael O’Flaherty of the Irish Centre of Human invited me to perform a song in memory of the victims of Srebrenica. Despite the short notice, I decided to sing an 18th century Irish song about a man thinking back to his lost lover from a distant war: Coinleach Ghláis an Fhomhair. The Summer School encouraged me to continue with my project through The Ideas Collective. There are so many merits to the methodology of using songs to give people a platform to use their voice. There are many pitfalls too, it seems – and people can be very quick to point these out. It’s difficult to know what to do. At a very simple level, I believe the act of singing can bring something out of a person that they may not have believed they were capable of. The main thrust of my project, however, is the chance to bring together an audience and to allow someone to tell her/his story to people who may not otherwise have listened before. |

AuthorDónal Kearney Categories

All

Archives

February 2018

|