BlogStories, Research & Projects

|

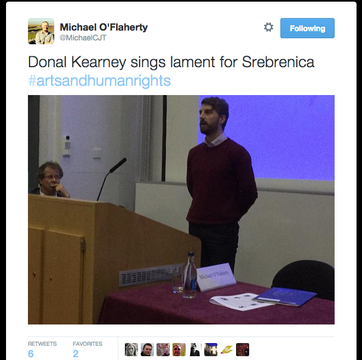

Last week, I attended the NUIG International Summer School on the Arts and Human Rights. As an alumnus of the Irish Centre for Human Rights, I was very comfortable returning to discuss issues of international human rights law. This time, the rights theory was infused with artistic critique. The closest thing I’d come to this combination previously was during the Human Rights Council at the OHCHR, Geneva, when artists advocated for civic freedoms through the practice of their work. I came across countless artist human rights defenders in my work with Front Line Defenders in Dublin. There are people across the world using their talent, their energy, and their time to promote the human rights of others. This is all the more admirable in states where the statements made by the artists breaches domestic law. For example, a rapper who records a track lambasting government policy may find herself subject to criminal proceedings in some east Asian states. The NUIG Summer School looked at the interface between artistic and human rights practices. In attendance were legal practitioners from across the world, current and former UN Special Rapporteurs, heads of international NGOs, academics in the field of human rights, as well as high-profile musicians, artists, curators and producers. An eclectic array of opinions served up a fascinating discussion over the two days I attended (I missed the opening day thanks to a wedding gig in Newry!). On the second day, I was selected to present in the workshop on Music and Human Rights on the theme of “Belonging”. The facilitators were Executive Director of Musicians for Human Rights, Julian Fifer, and former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Manfred Nowak. Fair play to NUIG for assembling such an awesome team! My presentation addressed the power of song in the process of fostering a shared identity and community-building. Of course, songs can divide as well as unite – and this was one of the first questions that came back at me once I’d finished the presentation. I’ll be completing a document on my presentation, so I will post it on this blog in coming weeks. Indeed, an emerging theme of the Summer School on “Belonging” was how readily the debate turned to Exclusion. With any in-group, there is an out-group (‘the Other’). Art plays a role in bringing people together, but it can also pit communities against each other – especially in examples such as nationalistic imagery, songs in a particular language, or openly sectarian music such as that broadcast in Rwanda in 1994. For instance, singing in the Irish language arguably excludes those who do not understand the lyrics. An interesting topic of discussion might be to consider art that does not exclude, but rather includes everyone in a society. Please contribute in the comments below if you’ve any immediate thoughts! On the third day of the Summer School – 11 July 2015 – the Summer School marked the 20th anniversary of the Srebrenica massacre. Between 11-13 July 1995, Bosnian-Serb forces entered what was thought to be a UN-protected “safe area” in Srebrenica. Within a matter of days, 8000 Muslim Bosniaks had been murdered in what is considered to be the worst military atrocity since the Second World War. After a lecture given by Manfred Novak on the significance of music during the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Professor Michael O’Flaherty of the Irish Centre of Human invited me to perform a song in memory of the victims of Srebrenica. Despite the short notice, I decided to sing an 18th century Irish song about a man thinking back to his lost lover from a distant war: Coinleach Ghláis an Fhomhair. The Summer School encouraged me to continue with my project through The Ideas Collective. There are so many merits to the methodology of using songs to give people a platform to use their voice. There are many pitfalls too, it seems – and people can be very quick to point these out. It’s difficult to know what to do. At a very simple level, I believe the act of singing can bring something out of a person that they may not have believed they were capable of. The main thrust of my project, however, is the chance to bring together an audience and to allow someone to tell her/his story to people who may not otherwise have listened before.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorDónal Kearney Categories

All

Archives

February 2018

|